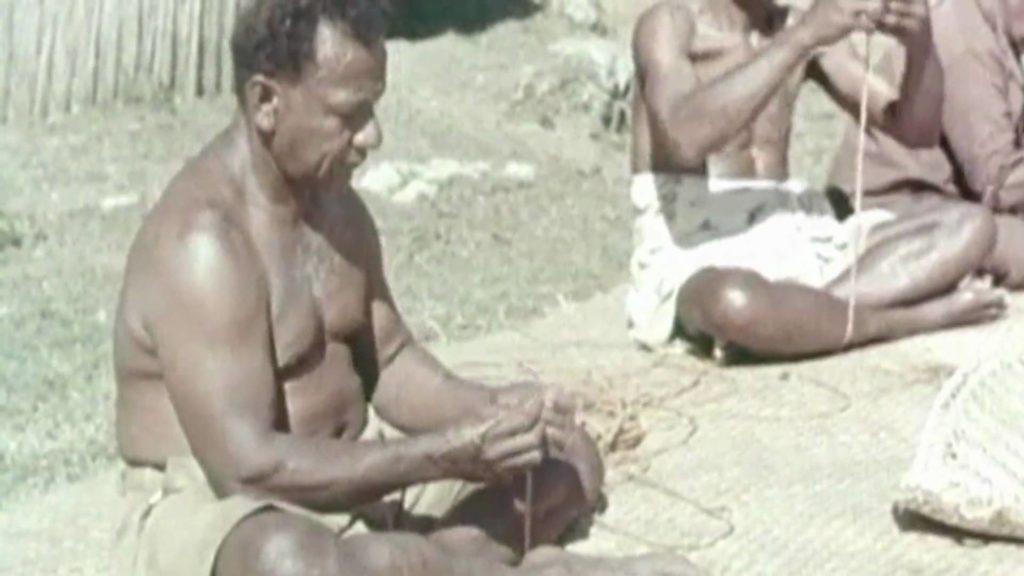

During the last century, missionaries, officials, and antiquarians collected many Fijian oral histories and legends while the traditions were still fresh. No early account mentioned a mass migration from across the sea, or the great canoe Kaunitoni. Most yavusa (kin groups or “tribes” claimed descent from a rock, cave, totemic animal, or mythic hero. Most yavusa (kin groups or “tribes”) claimed descent from, a rock, cave, totemic animal, or mythic hero. The Fijians believed they had lived in Fiji from time immemorial, since Degei, their supreme god, created the world.

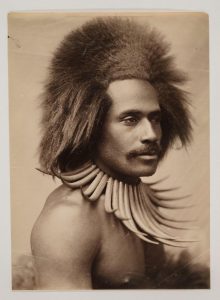

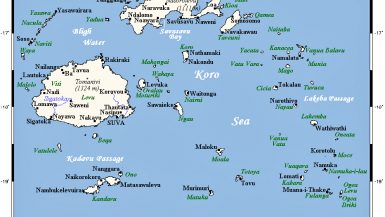

Fijians of the early contact period (c. 1800-1850) naturally thought Fiji was the largest and most important country in a world made mostly of water.

They were unpleasantly surprised, when first shown European maps, to see their islands so small, and other lands so large. They suspected the foreigners of deception in these matters. Thomas Williams, the missionary and pioneer ethnographer, wrote in 1858:

The Fijian is very proud of his country. Geographical truths arc unwelcome alike to his ears and his eyes. He looks with pleasure on a globe, as a representation of the world, until directed to contrast Fiji with Asia or America, when his joy ceases, and he acknowledges, with a forced smile, “Our land is not larger than the dung of a fly;” but, on rejoining his comrades, he pronounces the globe a “lying ball.”

By about 1890, a generation of Fijians had been educated in mission schools; they had come to accept that they lived in a small and remote part of a vast world. And Degei, their god, had been ousted by Jehovah, and demoted to the status of a heathen devil.

A vacuum was waiting to be filled, and there were those ready to fill it. In the late nineteenth century a theory known as diffusionism was in vogue among some archaeologists and ethnologists. Diffusionists argued that civilization could have been invented only once, and human culture had spread over the world from a single source: usually Egypt. Two adherents of these views, Carey and Fison, were teaching at the time in Fiji mission schools.

They noted the negroid appearance of the Fijians, and thought they could trace links between the languages of Fiji and Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Carey went so far as to compare Fijian customs with those of ancient Thebes, and concluded that the Fijians’ ancestors had been brought from black Africa to Egypt, whence they escaped to roam the oceans until landing in the South Pacific. These ideas were set down in a book that became a text in many schools.

Before long, half-baked versions of the African connection were circulating among the natives. In 1892 the Fijian-language newspaper Na Mata held a competition to select and publish the “definitive” origin legend. By 1893 the myth had acquired the canoe Kaunitoni and its occupants. However, most Fiji Europeans were not familiar with Carey and Fison’s book or with Na Mata. Anthropologists began collecting the Kaunitoni story from informants without being aware of its parentage; it became established among scholarsas firmly as among Fijians. In later years the tale received further respectability by being carried in the Methodist Mission Monthly and on a series of radio broadcasts.

The timeliness of the Kaunitoni story explains its success. It was a modern myth that gave all Fijians a common origin and a place in the new, larger world when their own beliefs were in shreds. The resemblance of the migration to that of the Jews must have been compelling to Christian converts. Indeed, the Fijians were restrained in their handling of such material, when compared to the Rastafarians or British Israelites.

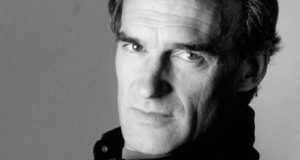

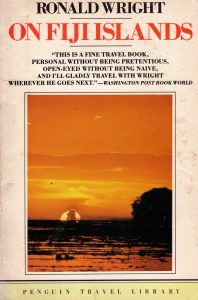

Historian, novelist, and essayist Ronald Wright is the award-winning author of nine books of nonfiction and fiction published in 16 languages and more than 50 countries. Much of his work explores the relationships between past and present, peoples and power, other cultures and our own.

On Fiji Islands was published in 1986 to critical acclaim. He has graciously allowed Fiji Guide to serialize his work for your enjoyment. We welcome your comments.

©2018 Ronald Wright