The Source of Fiji Culture

The visitor to Fiji with even the vaguest powers of perception cannot help but notice the pride of the indigenous people, which comes across in their carriage, their way of looking you squarely in the eye, and their respect for tradition, manifest in their hospitality. While other Pacific cultures have diminished with encroaching modernism, the Fijian way of life – Fiji Culture, remains strong and resilient in the face of outside influence. Factors such as language, land ownership and other traditions remain strong and have engendered a kind of resilience.

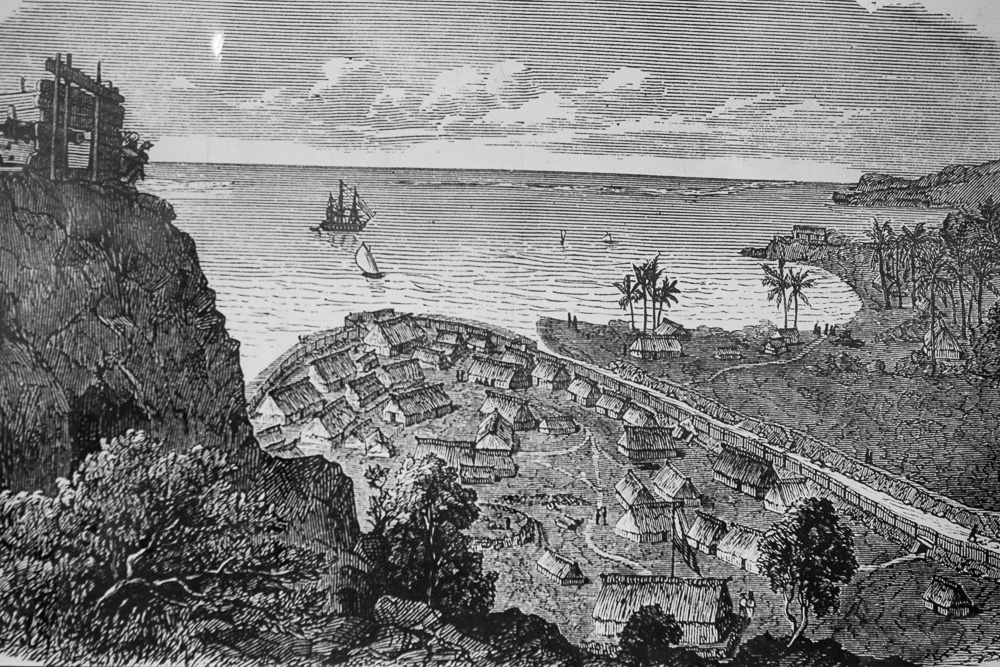

Traditional Fijian society is based on communal principles derived from village life. People in villages share the obligations and rewards of community life and are still led by a hereditary chief.

Fiji Culture–Rooted in Village Life

Traditional Fijian society is based on communal principles derived from village life. People in villages share the obligations and rewards of community life and are still led by a hereditary chief. They work together in the preparation of feasts and in the making of gifts for presentation on various occasions; they fish together, later dividing the catch; and they all help in communal activities such as the building of homes and maintenance of pathways and the village green.

The great advantage of this system is an extended family unit that allows no-one to go hungry, uncared for or unloved. Ideally it is an all-encompassing security net that works very effectively not only as a caretaking system, but also by giving each person a sense of belonging and identity. On the negative side, the communal system can be restrictive for the individual, who has no choice but to toe the line. Ambition and any kind of entrepreneurial instinct are quickly stifled, sometimes by jealous relatives if someone actually gets too far ahead. This means one can’t really be too different or rebel too much.

One will never grow rich in the village, but there is stability. Land ownership and the security of village life have provided Fijians with a `safety net’, but this has been a burden as well. In a sense, it has prevented Fijians (who own more than 80% of the land) from competing with the Indians, who have never had the luxury of land ownership. The communal life has put Fijians at a disadvantage with people whose lot has always been to struggle and make the most of what little they have; in the transition from a communal, subsistence-farming society to a capitalist money economy, Fijians have had to adjust much more than the Indians.

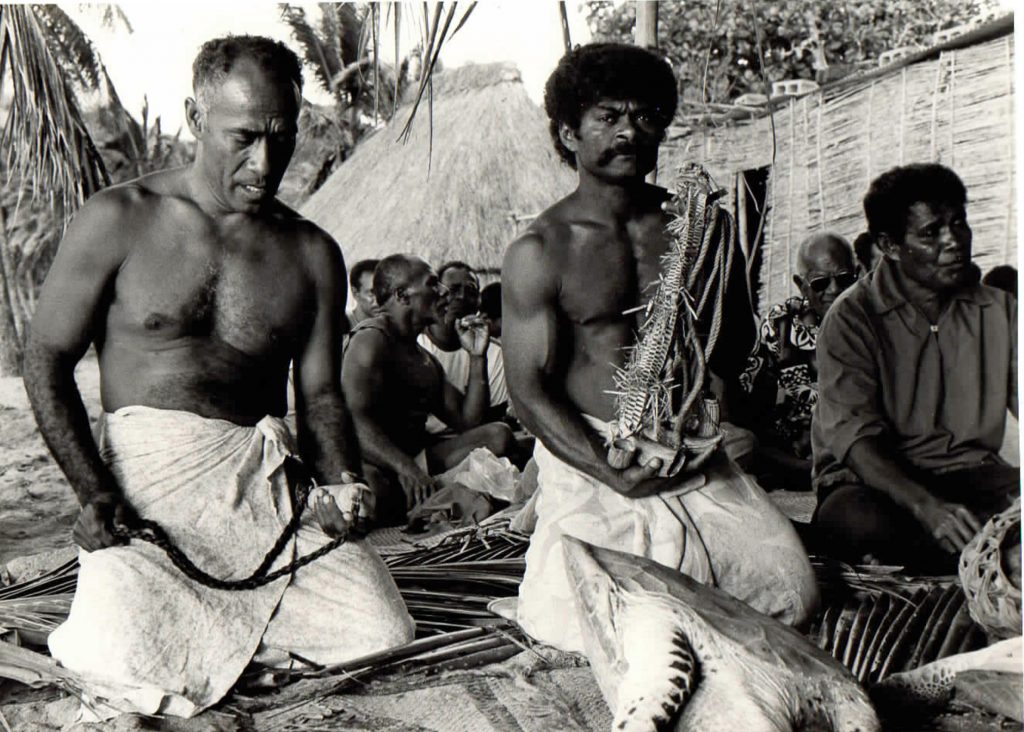

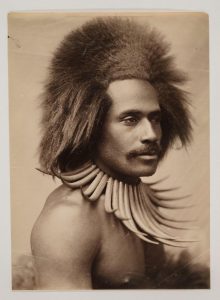

Tabua

A tabua, a tooth of the sperm whale, is the highest token of respect one can receive in Fiji. While the use of yaqona is shared with other regionsof the Pacific, tabua-giving is strictly a Fijian ritual. The tabua is presented to a distinguished guest – for example a high chief – or is given if a favour is requested. The tabua may be exchanged at betrothals, weddings, births, deaths or when a major contract or agreement is entered into.Likewise, tabua may also be used to make apologies after an argument.

Like yaqona, the tabua has an intrinsic role in the social and economic fabric of Fijian life. The value of each tabua is judged by its thickness and length. Taking one out of the country as a souvenir is strictly forbidden and given stricter laws protecting whales and other endangered species, it’s probably illegal to bring them into the USA and other nations.

Meke

The meke is a communal dance/theater combining singing, chanting and drumming. Traditionally it is performed in a village setting on special occasions – typically for visiting dignitaries. Today mekes are commonly presented at hotels for the benefit of tourists. However, the meke is much more than a colourful.

Dance – it is a medium of transmission that allows important historical events, stories, legends and culture to be handed down from onegeneration to the next. Often the composer of a meke is unknown, but the dances are embellished and passed on by the daunivucu whoserole it is to preserve the custom. Traditionally the daunivucu has links with the spirit world and when in communion with the spirit plane may go into a trance and begin to chant and sway. During this time the daunivucu’s disciples will watch his motions, which may be added to a particular ceremony. (Circa 1920 postcard from Jane Resture depicts meke)

In the meke every motion and nuance has its significance. The positioning of the performers and even of members of the audience is extremely important. Villagers of high birth have special positions in the ceremony, and to place them in a subordinate spot would be insulting and possibly mis-representative of the community’s history.

Firewalking

Fijian firewalking is an ancient ritual, which according to legend was given by a god only to the Sawau tribe of the island of Beqa off the south coast of Viti Levu. The skill is still possessed by the Sawau (who live in four villages on the southern side of Beqa), but in special cases members of other tribes adopted by the Sawau can also perform this mystifying ceremony. Nowadays firewalking is performed occasionally for Fijians, but most often for the benefit of tourists at various resorts.

The performances for the visitors are generally less steeped in custom than the one described here, but the demonstration of firewalking–a traditional Fiji culture icon–is just as genuine.

Traditionally, several male representatives are chosen from each village. All are immediate family of the bete, the traditional priest-cum-master of ceremonies. For two weeks before the event the participants must observe two strict rules: there must be no contact with women (an act of true sacrifice for most Fijian men) and eating coconuts is forbidden. Failure to observe these taboos may result in severe burns.

In preparation for the firewalking a circular pit a metre or more in depth and four to five metres wide is dug. It is lined with large, smooth stones athird to half a metre in diameter and covered with large logs. Six to eight hours before the ceremony a huge bonfire is built. The burning logs are later removed by men with long green poles who chant O-vulo-vulo and clear the way for the participants. A long tree fern, said to contain the spirit of God, is laid across the pit in the direction of the bete. Large vines are then dragged across the stones, levelling them for the actual firewalking.

When the stones are finally in position, the bete jumps on them and takesa few trial steps to test their firmness. He then calls for bundles of green leaves and swamp grass, which are placed around the edge of the pit. Finally, the position of the tree fern is adjusted at the command of the bete; the firewalkers will approach the pit from the direction in which it points. Meanwhile, the village men who have prepared the fire take their positions surrounding the pit, leaving a gap for the entry of the firewalkers.

The bete surveys the scene and when satisfied, shouts vuto-o, the signal for the firewalkers’ approach. They appear from their place of concealment and walk briskly towards the pit. The tree fern is removed and the firewalkers walk single file across the red-hot stones around the circumference of the pit. The devotees jump out of the pit and the bundles of grass and leaves are spread out on the stones, which steam in the fiery heat. The performers re-enter the pit amid the clouds of steam and squat for a few minutes in their version of a Turkish bath. After this they walk off the stones unscathed by the ordeal. At this time, if the ceremony is held at a resort, the inevitable sceptic will cautiously approach the pit and place the palm of his hand over the stones. He or she will then walk away convinced it was no charade.

How do they do it? No-one has the definite answer but scientists point to the power of suggestion, especially when the religious element of the ceremony is considered as well as the fact that an insulating film of moisture on the skin may act as a protective layer.

Members of the British Medical Association came to several conclusions after witnessing a ceremony. First, the skin of the participants was neither thicker nor tougher than that of anyone else accustomed to walking barefoot all their lives. Second, there was no evidence of oil or any other substance applied to theirfeet, nor were the participants under the influence of opiates. Finally, the performers reacted normally to painful stimuli such as burning cigarettes or needles jabbed into their feet before and after the firewalking.

Those who claim the performers may be in a trance-like state are also incorrect. Get close enough to the firewalkers during a performance and you may hear them crack jokes. One reliable witness told me he saw a participant pull a cigarette from behind his ear, light it on a red-hot stone and have a leisurely smoke!

Cannibalism — the dark legacy of Fiji Culture

Cannibalism was an extremely important institution in pre-Christian Fiji, practiced as early as several hundred years before the birth of Christ. According to Fergus Clunie, former director of the Fiji Museum, it was a ‘perfectly normal part of life’. The practice was a function of the religion: the great warrior-gods were cannibals and they required human sacrifice. Although some clans did not in fact eat human flesh for religious reasons (their totems were human), the practice of cannibalism was widespread throughout the Fiji group.

Victims were not just randomly selected, but were almost always enemies taken during battles. Eating your enemy was the ultimate disgrace the victor could impose, and in the Fijian system of ancestor worship this became a lasting insult to the victims’ families. This explains much of the sometimes extremely vicious infighting; internecine warfare and vengeance-seeking that went on in pre-Christian times. By all accounts, violence was a way of life and an accepted form of behavior when directed towards one’s foes. Chiefs generally had a grudge against someone or were involved in a power struggle, and war could be an everyday occurrence. It was during these periods of warfare that cannibalism was practiced.

Fijians were not without a gruesome sense of humor. They often got a chuckle out of cutting off a piece of some unfortunate soul’s flesh (tongue or fingers for example) cooking it, commenting on how good it tasted and then offering it to the victim to eat. There are also horrifying accounts of missionaries who, in times of war, were given samples of cooked meat and were later told what they had eaten.

Eating human flesh was only one of many bloody practices in a society where extreme violence and extreme kindness existed side by side. Some examples of the darker aspects included hanging captured ‘enemy’ children by the feet or hands from the sail yards of war canoes; burying men alive at the post holes of new homes or temples being constructed; and strangling women at the graves of chiefs so that they could ‘accompany’ the chiefs into the next world.

Education

Fiji has a good system of education compared with most of its neighbors and is a center for learning in the South Pacific. Enrollment is nearly 100% for primary-school children, and tuition for grades one to eight is free. Classes are taught in the pupil’s parent tongue (the local Fijian dialect for the Fijians and Hindi or Urdu for the Indians) and in English for the first few years until students have grasped enough English to make it the medium of instruction. Thus nearly everyone – except some of the older generation – speaks English.

Fiji has 660 primary schools, 140 secondary schools, 37 vocational schools, a theological college and one university (the University of the South Pacific). Vocational training includes courses in engineering, maritime studies, telecommunications, agriculture, carpentry, hotel and restaurant management and business. The University of the South Pacific, established in 1968, has an enrollment of about 2500 students from throughout the Pacific and is funded primarily by Fiji and grants from overseas. There is also a separate Fiji School of Medicine, associated with the university.

Religion

Fiji is a meeting ground of three of the world’s great religions – Christianity, Hinduism and Islam – which are all practised here in tolerance of each other. Surveys indicate that almost all of Fiji’s inhabitants belong to some type of organised religion. Church attendance is generally high and pastors and priests wield a great deal of power over their flock. According to “Index Mundi” the numbers are: Protestant 45% (Methodist 34.6%, Assembly of God 5.7%, Seventh Day Adventist 3.9%, and Anglican 0.8%), Hindu 27.9%, other Christian 10.4%, Roman Catholic 9.1%, Muslim 6.3%, Sikh 0.3%, other 0.3%, none 0.8%

Ancient Fijian Religion

The old Fijian religion contained a myriad of gods and spirits. Along with the same gods worshiped in different parts of the country, each clan might have its own deities. The core of the system was ancestor worship in which people paid homage to their forebears,particularly the illustrious ones. Each clan had its own temples dedicated to one god or goddess – an ancestor with a specific role. Thus one ancestral spirit, perhaps descended from a great warrior, would be dedicated to warfare and cannibalism; others, perhaps descended from an agriculturalist, would be concerned with crop productivity; and others might be concerned with fishing or some other activity. Gods thus reflected the society from which they sprang.

Deification of chiefs went on right into the last century. This was evidenced on the battlefield, when warriors were reluctant to kill chiefs because they were seen as demigods – people who stemmed from the gods and had the potential to become gods. When a chief fell in a battle, the ranks broke and the enemy was for all practical purposes vanquished. This aspect was not lost on unscrupulous chiefs who hired European mercenaries to shoot enemy chiefs on sight. Perhaps this explains why a small group of Europeans backed by a strong ‘conventional’ Fijian army could wreak havoc upon armies of thousands of Fijian warriors.

Christianity–an integral element of Fiji Culture

Although the priesthood and many of the ruling elite were at first reluctant to accept Christianity, Fijians in general embraced the new religion once their leaders had done so. They saw that the Christian god was powerful: he could produce incredible things like guns, ships and other technology. He was certainly a god to be reckoned with, but by their thinking he was only one of many gods.

During the introduction of Christianity some Fijians were so impressed they built temples to the Christian god even before the missionaries attempted conversion. They saw little difference between the Christian god and their own deities except that the Christian god didn’t like them to worship other gods.

In post-coup Fiji the Methodist church, which is as close to an ‘official’ religion as Fiji has, has gained considerably more influence. One reason is that the church has a good friend in Sitiveni Rabuka, who is a fervent believer. The church is also very sympathetic to the nationalist leanings of the current government. Perhaps the most obvious influence of the Methodist church is its strict support of ‘desecularising’ Sunday – making it devoid of any commercial activities.

In Fiji there is a church or denomination for just about everyone (see the following list of Christian churches and services). Visitors are always welcome to a Fijian service, and participating in one – particularly in a village – is a wonderful Fijian experience.

Indian Families

Although Fijian Indians come from a variety of subcultures and religious groups, they are seen as a people who share a common way of life,and for political and administrative purposes they have always been lumped together. Early migrants coming to Fiji were carriers of Indian culture only in a limited sense. Most were young, illiterate peasants whose connections with India ended the day their ship left port. Once in Fiji, social groups based on caste disappeared for the most part; and because of a shortage of women, migrants were compelled to marry across religious lines. In addition, communal kinship patterns found in the traditional Indian village gave way to more individualism due to the breakdown in social structure and heightened demands for personal survival.

Yet Fijian Indians are still distinguished by their institutions of family and marriage. Although individuals have more free will to choose theirpartners today than in times past, relatives continue to have influence in this realm. Arranged marriages are more common in rural areas, andmarriage occurs mainly within subcultural categories and religious groups. Strict marriageties are especiallyobserved by the more clannish Gujaratis andPunjabis (Sikhs).

Today the trend is towards nuclear-family households but in many areas, both urban and rural, the joint-family household persists. Financialand domestic arrangements may differ from home to home, but families may consist of parents, grandparents and both married and unmarried siblingsresiding under the same roof. Sons are given a freer rein than daughters, who are traditionally kept under very strict supervision.

Thus, despite a diverse cultural background, Fijian Indians are generally united through the common experience of indenture, the use of Fiji Hindi as their lingua franca, family organisation, cuisine and interests in sports and Indian movies.

The exceptions are the Gujaratis and the Punjabis, who arrived as free migrants from north-west India. They came as traders and merchants, and today own most of the shops and businesses in Fiji’s urban centres. Generally the Gujaratis and Punjabis have much stronger kinship ties and attachments to India.

Indo Fijian Religions

Basically the same religions (with the exception of Buddhism) exist in Fiji as in India, but several generations of separation from India have made the Fijian Indian a bit less orthodox in his or her practice. Less orthodox does not mean less religious; most Hindu homes have shrines where the family worships together. Although the caste system essentially ended for the Indians who arrived in Fiji, it still carries weight with Hindus in the realm of religion. ‘Pundits’ or priests who officiate at weddings and the like must be of the Brahmin caste.

The Hindu Fijian Indians, who make up about 80% of the Indian population, celebrate Diwali, Holi and the birth of Lord Krishna. Diwali is the colourful ‘Festival of Lights’, which occurs in October or November and resembles Christmas in the West. Houses are decorated ornately to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity. Traditionally it is a time when businesses end their fiscal year, paying up their accounts and opening new books.

Holi, held in February or March, is a spring festival. During this time chautals (holy songs) are sung and people amuse themselves by squirting coloured water at each other in the streets.

Sikhism, the fifth-largest organized religion in the world, is a monotheistic religion founded by Guru Nanak Dev in the 15th century. Sikhs advocate the pursuit of salvation through disciplined, personal meditation on the nature and will of God. Sikhs have their own temples (gurdwaras) where they carry out prayer meetings and read their holy book.

The Muslims, who make up about 15% of the Indian population, worship in numerous mosques throughout Fiji. The major holidays are the fasting period of Ramadan, the two Eids and the Prophet Mohammed’s birthday.

Indian Firewalking

Firewalking in Fiji is also practiced by Indians at an annual purification ritual called Trenial. It is performed at the Mariamman Temple in Suva and other locations in July or August. Hindu firewalking differs from the Fijian custom (see the earlier Culture section) in that the Indians walk across a shallow trench of burning embers whereas the Fijians stroll across a large pit of hot stones. Trenial is accompanied by the placing of three-pronged forks or tridents into cheeks, hands, ears, nose and tongue prior to walking over the red-hot coals.

During the 10-day period of preparation, devotees must sleep on the hardwood floor of the temple where the firewalking will occur; eat two meals a day of bland food (not the usual spicy Indian fare which is associated with lust and bodily satisfaction); bathe in cold water twice a day; abstain from alcohol, tobacco and sex; wear a minimum amount of clothing; devote time to prayer, confession and holy scriptures; and refrain from ill-feelings towards each other. If that isn’t enough, the faithful must submit to the disciplinary whip of the priest. Whippings are held in the morning and evening, following prayer.

The idea of this self-denial is to make the devotees forget their ‘body consciousness’. According to one religious authority, Pujari Rattan Swami:

All of us are conscious of our body…We are not prepared to leave our self body consciousness, therefore whipping and self-control methods make the devotees at least temporarily semi-conscious.

The firewalkers go through a host of other activities, including soaking their clothing in turmeric water (which acts as a germicide and insect repellent to keep the mosquitoes away from their more exposed and therefore more vulnerable bodies) and smearing themselves with ash from burnt cow dung to illustrate that if one conquers one’s weaknesses, one will become pure. In this same respect the devotees ritually crack open coconuts, meditating on the three layers (outside layer, fibrous layer and shell) which symbolise a person’s three weaknesses – ego, ignorance and attachment. (The last is hardest to crack literally and figuratively.)

On the day of the event, a ritual bath is taken in a nearby river followed by chants and drum beating. The participants are whipped into a trance-like state and may pierce their tongues, cheeks and skin on the forehead with sharp needles. They walk back to the temple chanting ‘Govinda’, the name of God. Upon returning to the temple the chief priest works the firewalkers into another trance and leads them across the glowing embers, once more shouting ‘Govinda’.

(Photo credits: All artifact shots courtesy of Fiji Museum)

Leave a reply